Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat is happening in the bond markets?

A bond is a bit like an IOU that can be traded in the financial markets.

Governments generally spend more than they raise in taxes, so they borrow money to fill the gap, usually by selling bonds to investors.

In addition to eventually paying back the value of the bond, governments pay interest at regular intervals so that investors receive a stream of future payments.

UK government bonds – known as “gilts” – are usually considered very safe, with little risk of the money not being repaid. They are mainly bought by financial institutions, such as pension funds.

The interest rates – known as the interest rate – on government bonds have been rising since around August.

The yield on a 10-year bond has risen to the highest level since 2008, while the yield on a 30-year bond is at its highest since 1998, meaning it costs the government more to borrow in the long term.

The pound has also fallen in value against the dollar over the past few days. On Tuesday it was worth $1.25 but is currently trading at $1.23.

Why are bond yields rising?

Dividends are not just rising in the UK. Borrowing costs have also increased in e.g. USA, Japan, Germany and France.

There is great uncertainty about what will happen when President-elect Donald Trump returns to the White House later this month. He has promised to impose tariffs on goods entering the United States and to lower taxes.

Investors are concerned that this will lead to inflation being more persistent than previously thought, and therefore interest rates will not fall as quickly as they had expected.

But in Britain there are also concerns that the economy is underperforming.

Inflation is at its highest in eight months – hit 2.6% in November – above the Bank of England’s target of 2% – while the economy has shrunk for two consecutive months.

Analysts say it is these wider concerns about the strength of the economy that are driving down the pound, which typically rises when borrowing costs rise.

How does it affect me?

Chancellor Rachel Reeves has promised that all day-to-day spending will be funded by taxes, not borrowing.

But if she needs more money to pay back higher borrowing costs, it uses up more tax revenue, leaving less money to spend on other things.

Economists have warned that this could mean spending cuts that would affect public services and tax increases that could hit people’s wages or the ability of businesses to grow and hire more people.

The government has committed to having only one financial event a year where it can raise tax, and that is not expected until the autumn.

So if higher borrowing costs continue, we may be more likely to see spending cuts sooner than that, or at least lower spending increases than would otherwise happen.

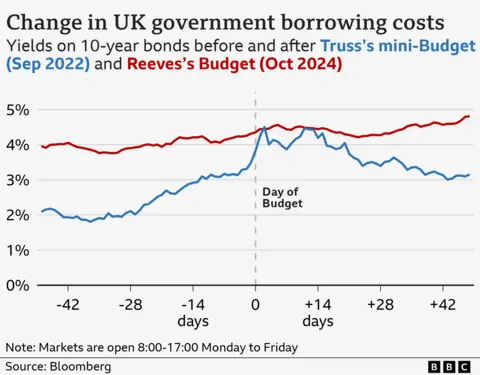

Some people may be wondering about the impact of higher gilt yields on the mortgage market, especially after what happened after Liz Truss’ September 2022 mini-budget.

Although yields are higher now than they were then, they have slowly risen over a period of months, whereas in 2022 they shot up over a few days.

The rapid rise led to lenders quickly pulling deals as they tried to figure out what interest rate to charge.

Analysts and brokers say the current turmoil in the markets is having some effect on mortgage pricing. Many expected to see some declines in interest rates at the start of the year, but instead lenders are holding off on cuts to see what happens.

But the market is favorable for anyone who currently buys an annuity – a retirement income for the rest of life, bought only once.

An annuity expert told the BBC that many people would get a better deal now than at any time since 2008.

What happens then?

The Ministry of Finance has said that there is no need for an emergency intervention in the financial markets.

It has said it will not issue any spending or tax announcements ahead of the official borrowing forecast from its independent watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which is due on 26 March.

If the OBR says the Chancellor is still on track to meet his self-imposed fiscal rules, then that could decide the markets.

But if the OBR were to say because of slower growth and higher-than-expected interest rates the chancellor was likely to break her fiscal rules, then that would potentially be a problem for Reeves.